![]()

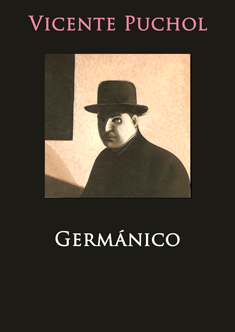

Germánico

Synopsis: Germánico

A nearly bankrupt businessman, Germánico, is visited by a young woman – an acquaintance of his daughter’s – who offers to help him steal a fortune, risk-free. She is the “lady friend” of a tycoon’s son; her lover’s father is a maniacal misanthrope who delights in carrying out dirty business deals in his home. He fondles bills, jewels, and drugs, all because the varied profits of his legitimate businesses bring him no “sensual pleasure” – they are merely numbers on a balance sheet.

These transactions are usually carried out at night, and because the young woman has both the confidence of her lover and his father and the keys to the mansion, an opportunity to commit the crime readily presents itself. Germánico grudgingly agrees to participate in the robbery. The pair carries out the theft, splits the proceeds, and, after a brief romance, parts ways. Germánico is left alone with a briefcase full of money that he has to launder, much to the shock of those who are aware of his circumstances.

The terrible impact that this situation has on Germánico, now submerged in brutal solitude, is the basis of the novel’s narration. He is tortured by the thought that he has become a criminal and by the traps that are continually set by his economic “rebirth.” The once-honest businessman is torn apart by his sudden solvency and the impossibility of escaping his new reality.

As well as my own comments, I would like to add those of leading Spanish literary critic, Santos Sanz Villanueva, which appeared in Diario 16 in 1989, on the publication of my novel Gérmanico. What follows is a brief excerpt from the end of his critique:

… it is the image of a generalized decline in values. Humanity’s lack of authenticity combines with the immorality of business, shining a light on this image; the light is the author’s voice. Thus, Puchol joins the ranks of authors who carry out a moralistic activity, who uncover and describe contemptible acts, condemning them without excuses. Puchol’s moralism is strict, but his novel avoids overly explicit lessons, and his attitude is not severe. On the contrary, mockery, humor, and nonsense are a regular part of this harsh chronicle of dirty business and perverse habits.

Author's Note: This is the definitive version of the first edition of the novel, which was originally published as Germánico.